Just before a stretched memory breaks with the past like a rubber band, at the same place where an echo turns to a whisper, when the clashes of Achaean and Trojan swords battling in their fierce war over Helen of Troy were ringing out along the Aegean coast of Asia Minor, an island arose from the waters of the Black Sea — a sea the ancient Greeks regarded as “inhospitable.” The island was called Lewke, the Greek word for white. Today this island is known as Zmiinyi or Snake Island.

According to legend, the island was created by the sea nymph Thetis. After 17 days of mourning for her son Achilles, who had died in battle at the gates of Troy after Paris targeted an arrow at the only vulnerable spot on his body –– his heel, the grief-stricken Thetis raised a snow-white rocky island from the depths of the sea. It was to become the last refuge for her only and beloved child.

Later, a stone temple in honour of Achilles was built on the island. Greek ships would invariably visit there when traversing the waters from the metropolis to their colonies on the Northern Black Sea coast or vice versa, when returning home. Over time, the ancient Greeks became more familiar with these lands, now the sovereign territory of Ukraine. Having explored the shores, inlets, and harbours, their unease transformed into admiration, and they now saw the Black Sea as “hospitable,” designating it as peaceful and safe for many years to come (albeit, with a few exceptions).

At the beginning of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Snake Island quickly became a symbol of national resistance. The commander of a Russian battleship threatened 13 Ukrainian border guards stationed there with death and destruction if they did not surrender. They flatly refused, with a reply that would rally a nation: “Russian warship, go fuck yourself!” Those guardians of Snake Island became talismans of Ukrainian tenacity, proving to everyone, no trouble is so great as to coerce the loss of belief in yourself.

Today, pundits, politicians, and purveyors of doom have worn out the meaning of an “existential crisis,” making surviving one, unfairly pedestrian. Bereft of solutions to life’s questions, and having themselves launched salvos of troubles, from inflation to healthcare, all products of failed leadership, egos become deliberately inflated casting dark shadows on common sense solutions to treatable symptoms of a complicated life. It is no suprise that in this ecology, suicide emerges as an option, especially when popular culture sanitizes the pressure to surrender rather than champion resistance.

Whether or not to take up arms against yourself, to capitulate to life’s challenges, is not a new question, having been pondered, poetically, by William Shakespeare, in Hamlet, Act III, Scene I:

To be, or not to be: that is the question:

Whether ’tis nobler in the mind to suffer

The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune,

Or to take arms against a sea of troubles,

And by opposing end them? To die: to sleep...

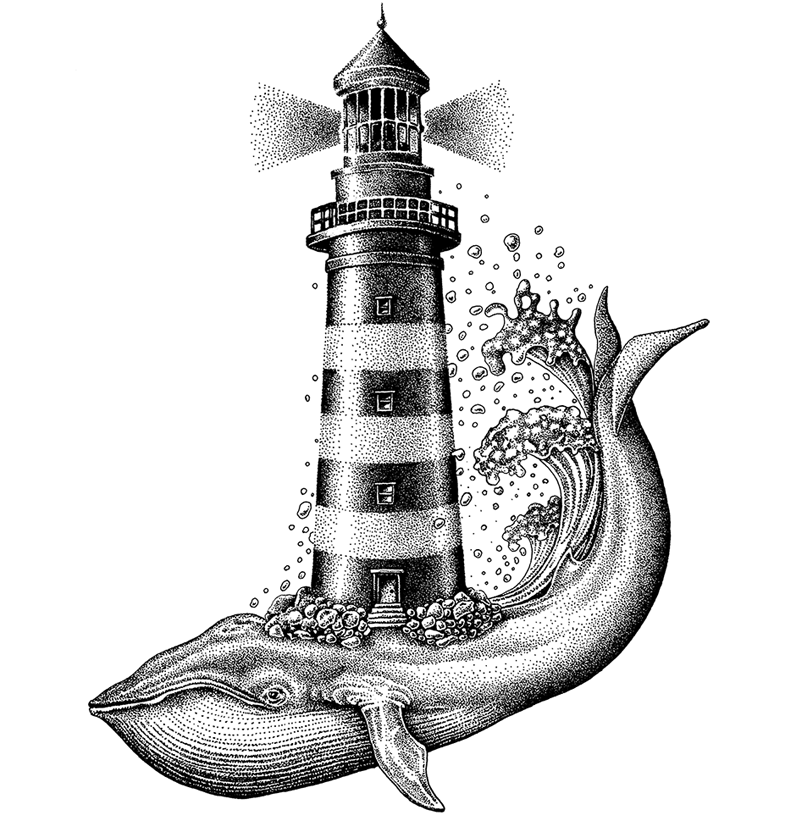

But how does a country, a people, or a nation answer his question when faced with a genocide? Turns out, questions posed by poets are often answered by soldiers: the Guardians of Snake Island in the Black Sea have become beacons, showing us how to sail through a sea of troubles.

The same coast where Greek, and later Roman, Byzantine, Genoese, Ottoman, and many other ships have long been docked, is regularly shelled by Russia’s military. The Russian Federation’s Ministry of Defence threatens to attack any foreign ships entering its waters. Anti-ship mines are surfing its waves instead of Ukrainian and foreign vacationers.

Ukraine, however, is not surrendering: archaeologists of the future exploring the bottom of the Black Sea will discover several artefacts from the turbulent Ukrainian present, at least one of which will be a Russian missile cruiser, the Kremlin’s flagship Moskva, resting on the seabed near Snake Island since 14 April 2022.

Ukrainians surprised the Western world by resisting the first days of Russia’s full-scale invasion, despite the fact everyone was betting on a lightning-speed victory for Russia, considered the second greatest army in the world (although most sympathised with the underdog). Experts (many without expertise) in capitals such as Berlin, London, and Washington, DC, even hoped for a quick decapitation of Kyiv’s leadership. Ukraine continues to astonish the West because Ukrainians will not supplicate to Putin. Kyiv’s leadership has embraced a principled position to not trade sovereign lands or individual agency in exchange for an ersatz peace from a street thug, a dictator who dreams of reviving the Russian Empire.

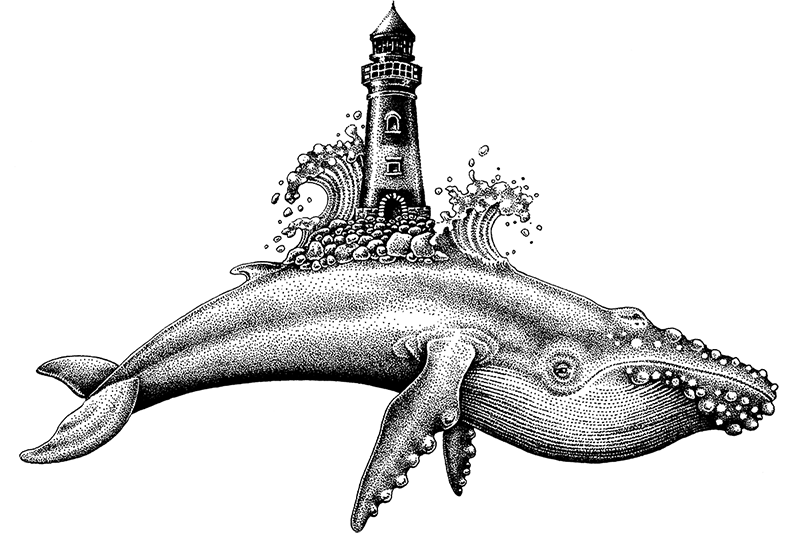

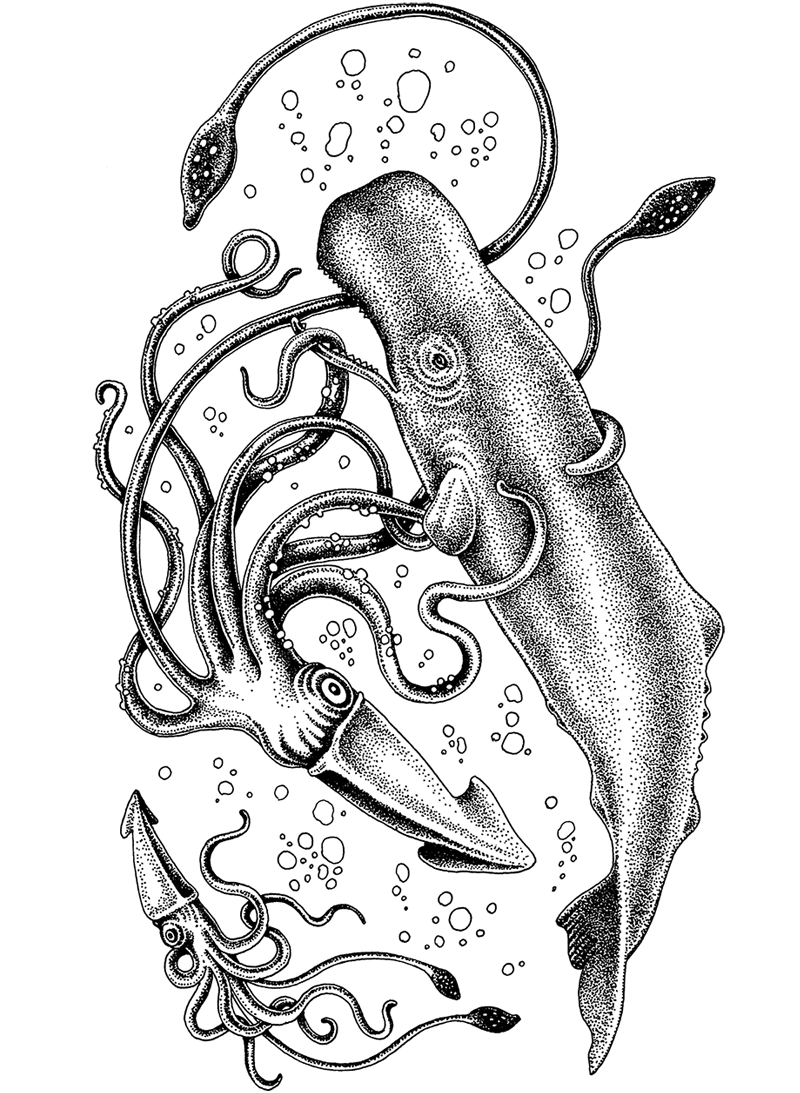

Ukrainians, like the Black Sea whale, did not exist for the international community. Hidden under the dark and stormy layers of propaganda and disinformation, often disguised as literature, Ukrainians have spent more than a century holding their breath, ascending from the depths of the sea to the surface, to finally exhale and assert their true name. Ukraine’s national consolidation is its strongest weapon and it will break the bonds of the Russian Empire’s cultural appropriation which branded Ukrainians as “Little Russians” or “Soviets,” a prison moniker forced on Ukrainians by the Soviet Union.

Western journalists were amazed to see Ukrainians as distinct, even cool. In an interview with the BBC in March 2023, Foreign Minister Dmytro Kuleba replied, “Historically, Ukraine was unfavourably under-appreciated. And I regret it took bloodshed and a devastating war for the world to realise how cool we are. And we were always cool. But it just took you too much time to realise that.” Indeed, we were cool, before 24 February 2022, or February–March 2014, or 24 August 1991. But Western perceptions of Ukraine were framed by Moscow –– the centre of a LARP empire — whose leaders excelled at cosplaying a powerful political force, although in reality, it was simply a Potemkin village.

It’s OK to admit you have been living under a misapprehension. There’s been a lot of flotsam polluting the waters of a good faith conversation between Kyiv and its western partners in London, Brussels, Washington, and other capitals.

Military cooperation between Kyiv, London, Brussels, and Washington shouldn’t be a fountain of anxiety (except maybe in Moscow, and that’s not a bad thing). Weapons in Ukrainian hands are not for suicide, but for self-defence; not in order to avoid the “sea of troubles,” but to prepare and plan for the challenges posed by an aggressive neighbour; to stop them here, between two worlds, on the barricade between two civilisations: one where the rule of law reigns, and the other where abject violence and brute force set the agenda.

To help clear the waters, we decided to launch The Black Sea Whale.

The Black Sea Whale is a new publication, with lyrics from a long forgotten whale song emanating from the raging waters of the hospitable sea ebbing and flowing over the temporarily Russian-occupied Ukrainian Crimean Peninsula and Ukraine’s sovereign Snake Island. Carried on the current for thousands of kilometres, this song can be heard around the world connecting the past, present, and future of Ukraine and its people with Western civilisation, which we have been a part of since ancient times.

The stories in The Black Sea Whale (a “thirdly” publication, as opposed to a quarterly) are a second chance for the world: not just to listen, but to hear the sincere and true voice of Ukrainians, and to discover authentic Ukraine and its polyphony. They are about the prosaic and the extraordinary, about who we were, who we are, and who we can be. Some stories resemble reality so vividly, they are hard to believe, while others are so outlandish, they strike you as being true. Sometimes they are ironically comedic, at other times heart-wrenchingly sad, but always self-critical and reflect the lessons we have learnt throughout life. You might find echoes of your own life in the specifics of Ukraine, in this bespoke publication for the English-speaking world, because the challenges we face are universal be they in Kyiv or London or where you might be reading this.

These are stories we would want to read ourselves.

In her story in the inaugural issue of The Black Sea Whale, Marichka Melnyk comes to the conclusion: “Good enemies don’t exist, and neither do innocent traitors,” after living under Russian occupation in her village outside Kyiv for 34 days. Witnessing the behaviour of her fellow villagers and their attitudes toward the Russian occupiers, she poses a difficult question: Is there a place for traitors in post-victory Ukraine? In her answer, she draws parallels with the policy toward collaborators in the post-WWII de-occupied Netherlands.

“I work as much as I’m paid,” “It’s not in my job description,” “I won’t get a bonus anyway,” “Can’t anyone else do it?” Consider yourself lucky if these verbal parasites haven’t poisoned your daily professional life. When most of the ship’s crew is beset with demotivation, relying on a successful voyage is foolish and fraught with consequence. Viktoriia Antonenko introduces you to the world of Soviet values, preserved like museum relics scattered throughout all spheres of life.

As soon as Russian troops occupied Chornobyl in February 2022, an ominous cloud of fear drifted over Ukraine once again. After the nuclear power plant accident in 1986, Ukrainians routinely blamed Chornobyl for all their troubles. Although Russia’s occupation of Ukraine’s Donbas replaced it as the focus of all of Ukraine’s ills in 2014, the Chornobyl Zone of Alienation continues to cause dread. Mary Mycio (1959-2022) reveals the heroes, real and imaginary, thanks to whom alienation is eventually replaced by rebirth. And she is not afraid to expose the real culprit behind both catastrophes.

Ukraine is not the only country stuck in a toxic relationship with Russia. The almost maniacal fascination with the “great” Russian culture and “mystical” Russian nature, including an unhealthy obsession with Russia as a vital partner at the expense of other global relationships, is a national characteristic of Germans, regardless of political party preference. Sergej Sumlenny reveals the origins of Berlin’s deep-seated infatuation with Moscow and how it has been affected by Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

The desperate act of self-immolation in Kaunas by the hippie Romas Kalanta in the spring of 1972 became a litmus test for Lithuanians who still remembered living in an independent state and perceived the Soviets as occupiers. The collective memory of the Baltic nations turned out to be stronger than that of Ukrainians. Oleksii Dubrov shows us how Lithuania weaves the threads of history into a portrait of their rebirth even if the yarn may be frayed.

Cartographers have been mapping the environment to bring about a better understanding of the world we live in. Janusz Bugajski, senior fellow at The Jamestown Foundation, analyses the fragile foundations of the Russian Federation and uncovers new opportunities waiting for the colonised, non-Russian peoples following the inevitable transformation of Russia from Empire to State.

“I woke up that day to the sound of explosions and the whistling of missiles as they flew by my window and crashed into the centre of Moscow.” Is there safety in any of the five zones of occupation into which the city of Moscow is divided in 2049? Oleksiі Dubrov’s story gives us a glimpse into the future, where a Ukrainian from Mariupol returns home, and Russians reside on territory delineated by the Ural Mountains on the one hand, and the Far East on the other.

Thank you for sharing an interest in Ukrainians and their creative contributions in this, the inaugural issue of The Black Sea Whale.

Enjoy the song and keep reading.